More than just tremor

Parkinson's disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disease – right after Alzheimer's disease. According to estimates, there are at least 200,000 people affected in Germany, with a clear upward trend. Parkinson's disease mostly occurs in older adulthood: The vast majority of those affected are at least 60 years old. However, ten percent of all Parkinson's patients develop the disease before the age of 50. Even young people in their twenties can be affected, although rarely. Doctors then speak of juvenile or young-onset Parkinson's. Overall, there are approximately 50 percent more male Parkinson's patients than female. It is not yet clear why.

The most common and well-known symptoms of Parkinson's disease are trembling, also called tremor, and slowed and decreased movements. The early stage of the disease differs from the more familiar later stage of the disease: Early signs of the disease may include depression, sleep disturbances, constipation, a disturbed sense of smell, a softer and monotone voice, or the failure of one arm to swing along when walking. The main classic symptoms become more apparent only after a certain time. Some patients also experience symptoms of dementia as the disease progresses.

The main classic symptoms:

- Bradykinesia (slowing down): In affected individuals, the ability to move decreases. For example, Parkinson's patients walk remarkably slowly and with small steps; they find it difficult to turn. The facial expressions become mask-like, the handwriting becomes smaller.

- Rest tremors (trembling while resting): This is an involuntary shaking movement of the hands. Later in the course of the disease, the rest tremor may also affect the feet. In Parkinson's, the tremor occurs only while the hands and feet are at rest and increases during emotional stress. The rest tremor may also be limited to one half of the body. It disappears when patients move the affected extremity or during sleep.

- Rigidity (stiffness): A typical symptom for Parkinson's patients is a stiffness of the muscles, which often affects the neck, arms, and legs. The posture is bent forward. Affected persons feel as if movements have to be performed against a resistance. Sometimes movements are blocked completely.

- Postural instability: This term is used to describe balance disorders. People who are affected walk and stand unsteadily and can no longer keep their balance, which is why there is a risk of falls.

Cell death in the "black matter"

Researchers have identified the death of neurons in the brain stem, or more precisely, in a dark-colored area called the substantia nigra ("black matter"), as the cause of Parkinson's symptoms. The cells of the substantia nigra release the neurotransmitter dopamine. This messenger is crucial for fine-tuning muscle movement, but also for starting movements in the first place. The typical movement disorders of Parkinson's only occur when more than 50 percent of the dopamine-producing cells of the substantia nigra have died.

How neurons die in the substantia nigra has not yet been fully explained. A characteristic of the disease is that so-called Lewy bodies appear in the affected cells. These are deposits containing a protein called alpha-synuclein. The majority of persons affected develop the disease around the age of sixty, when it occurs without an identifiable trigger, which is referred to as idiopathic or sporadic. In addition to the idiopathic form of Parkinson's disease, for which no specific causes have yet been identified, there are also genetic forms: Ten percent of Parkinson's diseases are genetic, that is, they are caused by heredity. Here, mutations, or changes in the genetic information, are the cause of the disease. Patients with genetic, also called family-related Parkinson's disease are on average somewhat younger when symptoms develop: Often the hereditary forms appear before the age of 50. In what is called secondary Parkinson's disease, the symptoms resemble those of "real" Parkinson's disease without being Parkinson's disease. Here, the symptoms are not caused by Parkinson's disease and thus by cells dying in the substantia nigra. Instead, medications, drugs, brain inflammation, or other diseases are behind the Parkinson's-like symptoms.

Not curable, but well treatable

Parkinson's disease is not curable yet. However, with appropriate therapies, the disease can often be well controlled for years. Drug treatment plays an important role. For example, administration of dopamine precursors (e.g., in the form of the antiparkinsonian active substance L-dopa) can compensate for dopamine deficiency. If drug treatment is no longer sufficient, a so-called brain pacemaker may be considered. Small electrodes, inserted into the brain in a surgical procedure, stimulate or inhibit specific areas in the brain to relieve symptoms.

Parkinson's research at the DZNE: Causal research, early detection, individualized therapy

If you want to cure a disease, you must first understand it. Researchers at the DZNE are therefore searching for the causes of neuronal cell death in Parkinson's – both in the sporadic and the hereditary form of the disease. Others are exploring the role of inflammatory processes or specific gene mutations. In addition, scientists at the DZNE are investigating how damaged mitochondria can contribute to the development of the disease. The "power plants of the cell" can release harmful oxygen radicals and also break down dopamine. Another field in causal research is the gut microbiome, the bacterial community in the digestive tract: How does the composition of gut bacteria affect Parkinson's risk?

Another important research goal, however, is the search for biomarkers. These are measurable biological characteristics (e. g., in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid) that allow early detection of Parkinson's and help to keep a better eye on the progression of the disease. Such markers may also be used to tailor the therapy for those affected.

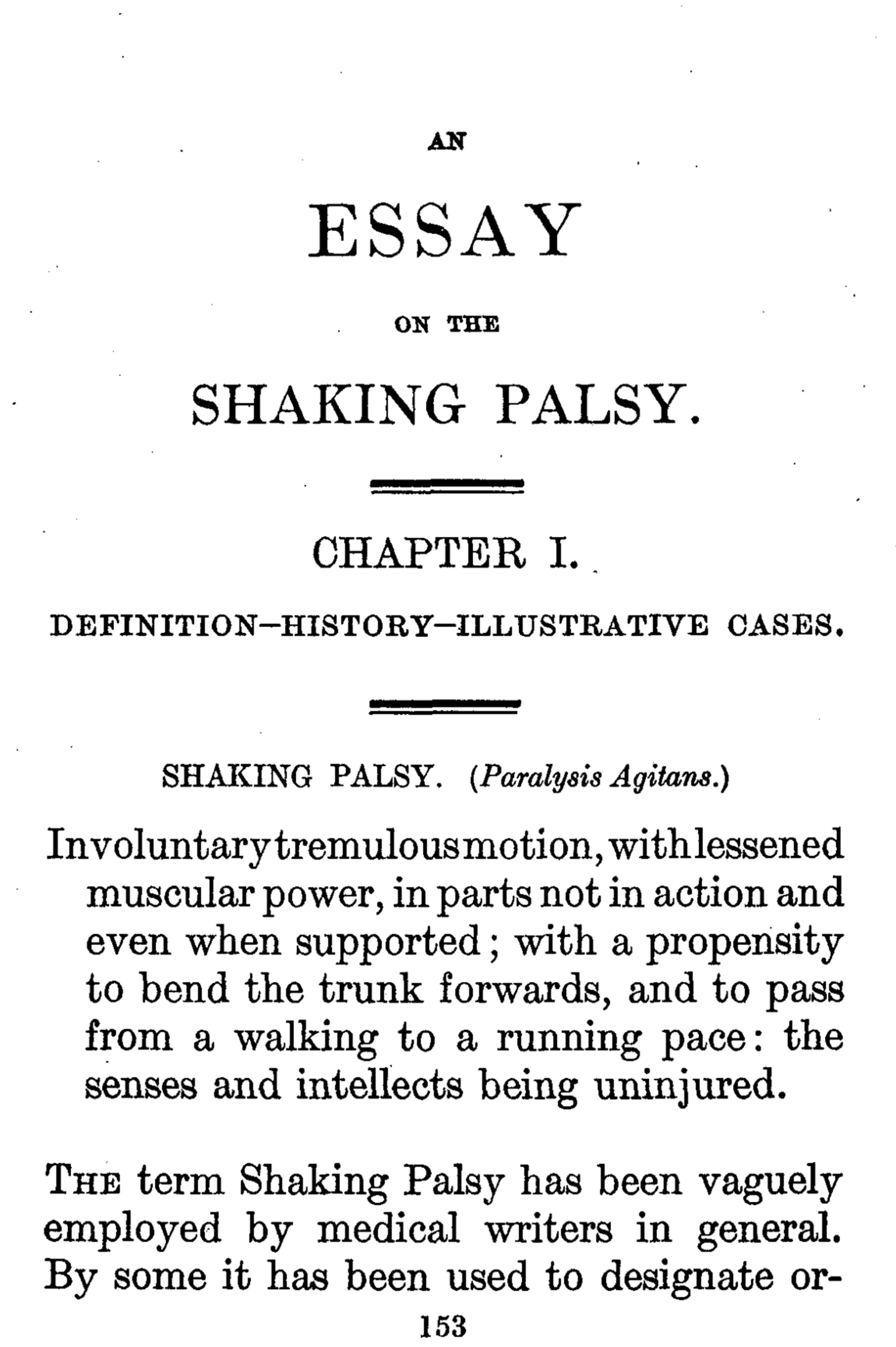

“Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power, in parts not in action and even when supported; with a propensity to bend the trunk forwards, and to pass from a walking to a running pace: the senses and intellects being uninjured.” With these words, the British physician James Parkinson described in 1817 in his publication "An Essay on the Shaking Palsy" – the disease later named after him. His accurate observation of the symptoms still forms the basis for the diagnosis of Parkinson's today, even though additions have been made to the symptoms since then. Parkinson had already recognized that it was a neurological condition, not a muscular problem.