Slipping into forgetting

According to projections, there are currently around 1.8 million people living with dementia in Germany – and numbers are rising. The majority of them are affected by Alzheimer's disease. Morbus Alzheimer, the technical name of the best-known and most common dementia, is a disease that usually manifests in old age. Only rarely are affected individuals younger than 60 years old. From a pathobiological perspective, Alzheimer's disease begins decades before the first memory deficits emerge, which means that the disease develops in the brain long before the first symptoms occur. And the older the population gets, the more the number of Alzheimer's patients grows. Alzheimer's disease is thus becoming a major challenge for society and the healthcare system – especially since there is still no effective therapy.

Typical symptoms of Alzheimer's disease include memory loss, disorientation, agitation, and speech disorders as well as aggression and a loss of inhibition, which is also called challenging behavior. These problems vary in severity among those affected. They intensify in the course of the disease, and other complaints are also added over time. Patients find it increasingly difficult to cope with everyday life and are therefore more and more dependent on help and support.

Progression in three stages

Alzheimer's disease creeps in slowly. The disease begins a long time before the first symptoms appear. At some point, the first, supposedly harmless lapses become noticeable. The person affected seems erratic and somewhat scatterbrained. They become forgetful, misplace things, don't finish their sentences, and otherwise have trouble concentrating. If these initially mild cognitive disorders become clearly disruptive in everyday life ─ over a period of at least six months ─ doctors begin talking about dementia.

In this first phase, those who suffer from this disease often appear depressed: The changes trigger grief, fear, and shame. Therefore, Alzheimer's disease cannot always be clearly distinguished from depression at this stage. But unlike depressive persons, many Alzheimer's sufferers have speech disorders and try to mask their deficits.

In the middle phase, speech comprehension deteriorates increasingly. Abilities such as driving, professional skills, or the ability to orient oneself are gradually lost. In addition to short-term memory, long-term memory is now also increasingly impacted. In addition, the personality of those affected also changes to an increasing extent: They are often nervous and restless, but also suspicious, irritable, and sometimes uninhibited or aggressive. Towards the end of the third phase, a great deal of motor restlessness joins the noticeable symptoms. Many patients begin to wander restlessly, without orientation, and without a sense of time.

In the late stages of the disease, such wandering around is no longer possible. Those affected increasingly become bedridden patients. They can only speak a few words or fall completely silent. Communication is hardly possible anymore – music, smells, or prayers are the most likely to penetrate the fog of forgetfulness.

Unresolved causes

The symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are the result of a massive death of nerves in the brain. Initially, it is mainly the synapses that are affected: These are the connection points through which information is passed from one nerve cell to the next. As the disease progresses, the neurons themselves die over wide areas in the brain.

In connection with these dying neurons, scientists see noticeable protein deposits in the brains of those affected. These deposits are thought to be partly responsible for neurons dying off: Proteins called beta-amyloid proteins clump together and accumulate between neurons, forming the noticeable plaques that Alois Alzheimer had already discovered in Auguste Deter's brain. These deposits lead to an inflammatory response of surrounding immune and glial cells, which promote the progression of the disease in various ways. Eventually, tau fibrils form in the neurons, impairing their function and contributing to the death of their cells. Why these protein molecules change in Alzheimer's patients has not been fully clarified.

Alzheimer's disease may be genetic. However, this is extremely rare and affects only about three to five percent of all cases. So far, three genes are known to be responsible for this form. If they are altered, Alzheimer's disease will break out in any case – usually very early, between the ages of 30 and 65.

Understand – recognize – heal: Alzheimer's research at the DZNE

Researchers at the DZNE are addressing Alzheimer's disease from many different angles, hoping to better understand the mechanisms behind this dementia. They are looking for the exact causes of the changes in the brains of those affected and want to clarify in what way the noticeable protein deposits damage the neurons. They are also investigating the role that inflammatory processes in the brain play in the disease.

Other research groups are looking into the possible genetic causes of the disease. In addition, DZNE scientists are also investigating other influencing factors, such as lifestyles, asking questions such as: What influence do diet and exercise have on the disease?

Another important field of research at the DZNE is the search for starting points for new therapies. However, the focus is not only on future treatment options, but also on the question of how patients can be specifically supported now through suitable care and support measures in order to maintain a good quality of life for as long as possible.

Last but not least, researchers at the DZNE are searching for biomarkers, meaning typical measurable changes in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid, for example, which can serve as early warning signs that a person will later develop Alzheimer's disease. Because even though there is currently no cure for the most common form of dementia, this is already known: The earlier treatment begins, the more successfully the progression of the disease can be delayed.

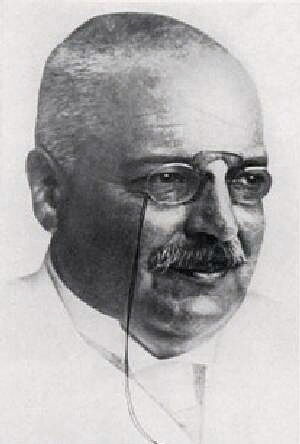

It was in 1901 that Alois Alzheimer, at that time senior physician at the "Institution for the Insane and Epileptic" ("Anstalt für Irre und Epileptische") in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, first met Auguste Deter, one of the most famous patients in medical history. The woman was only 51 years old, but suffered from a pronounced confusion otherwise common in very old people. Alzheimer accompanied the patient for years, examining her and documenting the progression of her disease, even after Deter had been transferred to another clinic.

"Her whole demeanor bore the stamp of utter perplexity," Alzheimer later said of the woman. "When reading, she goes from one line to another, reading letter by letter or with meaningless intonation." She often threw fits of screaming because she was so annoyed by her own inability. "I lost myself so to speak," Deter herself commented on her condition.

After the patient's death, Alzheimer was given the opportunity to dissect her brain – a procedure that was still unusual at the time. The "Mad Doctor with the Microscope," as his contemporaries often called him, recognized that Auguste Deter's brain had shrunk considerably. He also discovered noticeable fibers and deposits in the woman's thinking organ, which he linked to the disease. It was an assumption for which he was ridiculed at the time, but which is now considered a proven fact.

What is dementia?

Dementia is not one single disease. Rather, the term covers numerous diseases, the best known form of which is Alzheimer's disease.

The term "dementia" comes from Latin and literally means "away from the mind" or "without mind". That describes the core of dementia quite well: It is the progressive loss of mental capacity. Memory, thinking, concentration, and a number of other brain functions as well as behavior are affected.

The reason for the loss of mental abilities in all primary forms of dementia is a progressive loss of neurons in the brain. The reasons for this are many and the subject of intensive research. So-called secondary forms of dementia can develop as a result of illnesses, but also as a result of medication or alcohol abuse.

Primary forms of dementia are not curable. However, appropriate therapies can delay its progression and improve the quality of life of those affected. If secondary forms of dementia are known and treated in time, there is sometimes a chance of recovery.